Previously, we explained the laws of thermodynamics, emphasizing their importance in studying a building’s energy consumption.

But how are these laws applied to the energy balance in a building, and what implications can we draw from it?

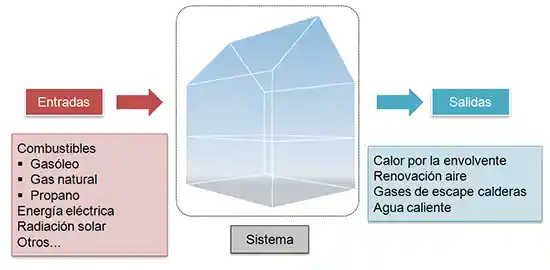

First, let’s consider the building as a thermodynamic system that has energy inputs. These energy inputs are mainly fuels, electrical energy, and solar radiation.

On the other hand, our system will have energy outputs. Primarily, these losses are heat transfer through the building envelope, and energy losses from fluids at temperatures different from the ambient temperature, such as losses from ventilation air extraction, heat losses in boiler exhaust gases, or heat losses from domestic hot water.

Since our system is quasi-stationary, the energy balance must be zero, meaning that the inputs must equal the outputs. Or in other words, a building’s consumption depends solely on its losses, being exactly what is needed to compensate for them.

This consequence may seem obvious, but it is worth pausing for a moment to analyze it. In our balance, we have not mentioned, for example, the work performed by electrical energy. Imagine our home, with an electrical appliance, for example, an oven, a light bulb, or a motor. These elements will perform their function and for that, they will consume electricity. This energy does not “disappear” from the system, but inevitably ends up turning into heat. Thus, the energy used in the oven, the light bulb, or the motor will end up increasing the temperature of the home.

Some of our readers might wonder, if all energy ends up as heat, why do we try, for example, to replace 50 W incandescent lighting with more efficient alternatives that achieve the same functionality with 7W. After all, the other 43W will be transferred to the room as heat, so we will avoid that consumption in fuels for the climate control system.

The answer is provided by the second law of thermodynamics and the concept of exergy. In our example, those 43 W had high exergy and could have been used, for example, in a heat pump to obtain between 170 to 200 thermal watts.

Therefore, the energy balance of the building, understood as a thermodynamic system, allows us to draw two fundamental conclusions for any energy-saving measure.

- In a building, the energy inputs of the system must equal its losses.

- The use of the exergy of the building’s energy inputs must be optimized.

To have an efficient building, it is necessary for the different installations to operate with the highest efficiency within their own field of action. This allows the designer to allocate the energy consumed by the building precisely to the point where it is required, and at the exact moment it is required. In this way, energy losses are reduced, achieving the maximum energy performance of the building.