It was about time we talked about the ESP8266 and the ESP32 on the blog, two machines that are currently causing a stir and carving out a prominent place in this trendy world of IoT.

When the first modules with the ESP8266 appeared, many of us thought, “Well, finally an affordable WiFi module for Arduino,” because, at that time, WiFi shields and alternatives for Arduino were prohibitively expensive.

However, many community members quickly recognized the potential of this little processor, whose features and low price have led to its great success in a short time.

Right now, both the ESP8266 and the ESP32 are setting trends and demonstrating day by day why they are, to this day, some of the top representatives of IoT.

Many commercial products are basing their development on these chips. A clear example is the Sonoff products from Itead, which allow home automation for very little money. According to Espressif, its manufacturer, they have sold over 100 million units.

But first, let’s start from the beginning by looking at what the ESP8266 is. In the next post, we will see its “older brother,” the ESP32.

In fact, it is such an interesting product and so relevant that we are going to create its own section on the blog.

What is the ESP8266?

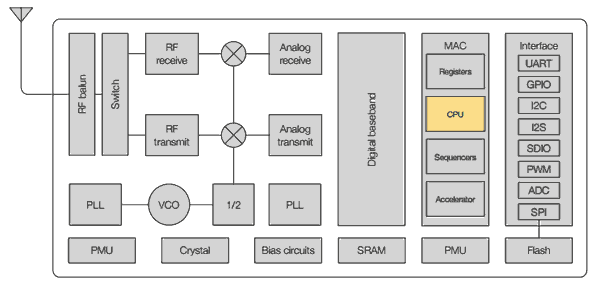

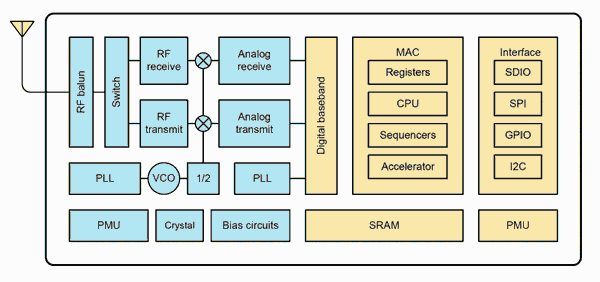

The ESP8266 is a SoC (system on chip) manufactured by the Chinese company Espressif. This SoC integrates various components into a single package, the main ones being a 32-bit processor and a WiFi chip with TCP/IP stack management.

In summary, the ESP8266 is a chip that integrates a general-purpose processor with full WiFi connectivity in a single package.

The processor integrated into the ESP8266 is a Tensilica L106 32-bit RISC architecture processor that operates at a speed of 80MHz, with a maximum speed of 160MHz.

The ESP8266 does not incorporate Flash memory within the SoC, so it must be provided by the module it is mounted on. The connection between the memory is done through QSPI, but normally, its use is transparent to us.

What is important to emphasize is that the available memory varies between modules; it is not determined by the ESP8266. Typically, models with 1MiB to 8MiB are found, with a maximum of 16MiB.

Features of the ESP8266

Here are some of the most relevant features:

- Low power 32-bit processor

- Speed of 80MHz (maximum of 160MHz)

- 32 KiB instruction RAM, 32 KiB cache RAM

- 80 KiB RAM for user data

- External flash memory up to 16MiB

- Integrated TCP/IP stack

- WiFi 802.11 b/g/n 2.4GHz (supports WPA/WPA2)

- Certified by FCC, CE, TELEC, WiFi Alliance, and SRRC

- 16 GPIO pins

- PWM on all pins (10 bits)

- 10-bit analog-to-digital converter

- UART (2x TX and 1x RX)

- SPI, I2C, I2S

- Operating voltage 3.0 to 3.6V

- Average consumption 80mA

- Standby consumption mode (1mW) and deep sleep (1uA).

History of the ESP8266

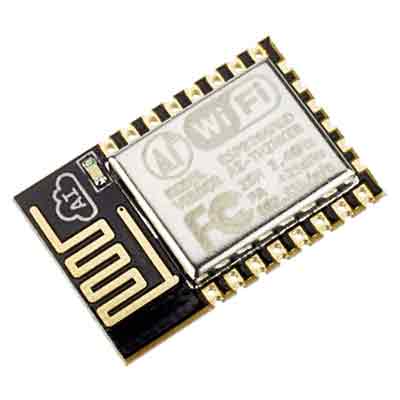

Without going too deep, the history of the ESP8266 and its superior sibling ESP32 begins in August 2014 with the appearance of the ESP01 modules from the manufacturer AI-Thinker.

At that time, the way to communicate with the ESP8266 was through AT modules, documentation was scarce and in Chinese, and the SDK was complex and not very accessible, which limited its utility. But that did not prevent its potential from being recognized, and the community and various manufacturers began to work actively on it.

Another significant milestone was the emergence of the NodeMCU firmware, which also names a development board. This firmware allowed programming the ESP8266 with LUA, a semi-compiled language based on C and Perl.

The community’s work continued generating documentation, tutorials, and tools. Thus, we reached the next great milestone, the release by the community of Open Source alternative SDKs for the ESP8266 based on the GCC toolchain.

This allowed programming with the Arduino environment using the ESP8266 Arduino Core. This was the definitive catapult for the ESP8266 in the maker sector, enabling it to benefit from the support of the vast community of Arduino enthusiasts.

Espressif reacted (or saw the potential, or decided to support the community) and created new SDKs with a license similar to MIT, which in some way provided support to the user community.

Since then, a large number of manufacturers have produced development boards that integrate the ESP8266. Some of the most famous, among others, are the NodeMCU and the WeMos, both with different variants. We will be looking at these boards soon.

We also have different SDKs and firmware available, which allow programming ESP8266 modules in various languages. Thus, we have MicroPython (Python language), ESPruino (Javascript), ESP-OPEN-ROT (based on FreeRTOS), or Mongoose OS, among other options. We will also see this soon.

In September 2016, the ESP32 was launched, a much superior model that addressed some of the shortcomings of the ESP8266. It has a slightly higher price, but if the ESP8266 is powerful and interesting, the ESP32 is directly a powerhouse. Support and documentation for the ESP32 are still inferior, but it is growing rapidly. We will see the ESP32 and its features in future posts.

Types of modules with ESP8266

There are different modules that integrate the ESP8266 SoC. The main characteristics of these modules are similar and are basically distinguished by the available Flash memory and their physical form, which in turn affects the number of accessible GPIO pins.

In some boards (the few), GPIOs are pin-shaped, so it is possible to solder a wire or connect a terminal. But in most cases, the modules have a “half-pin” shape, as they are designed to be integrated (soldered) onto PCBs or development boards.

To make it easy, in summary, by far the most common modules are the ESP01 and the ESP12/ESP12E. The rest are quite uncommon.

The ESP01 is very popular for being the first to appear, for its small size and low price. It is often used to provide connectivity to an Arduino-based solution (acting as a “WiFi shield”) as we saw in this post. However, it can also be used for developments that require few GPIOs (it only has 2 available).

On the other hand, the ESP12 and its variant ESP12E are becoming the preferred model of the ESP8266, and are mounted on a large number of development boards and commercial products.

In upcoming posts, we will delve into the very interesting world of the ESP8266 and the ESP32, various available development boards, how to program them, and tutorials to illustrate some of the possible uses of these two SoCs that are driving the development of IoT.