We are starting a series aimed at seeing how to implement automatic control mechanisms in a processor like Arduino. In this post, we will see what controlling a system means. In upcoming ones, we will cover on-off control, leading up to PID control.

There’s no doubt that one of the uses for processors like Arduino is to control systems automatically. But first, what is a controller? Which controller can I use? How is a controller implemented?

If you search, you’ll find a lot of information on the subject, books and books of hundreds of pages filled with equations. But the purpose of these posts is to explain it in a simple way (or try to), without using a single formula (almost none) and without excessive mathematical formalisms.

Of course, it does not aim to be a rigorous text, as the field is enormous (in fact, it was two entire subjects and a specialty in the engineering degree). If you want more details, you can rely on the abundant bibliography available.

Here we will try to do something that is not so common to find, give an intuitive view of control theory and the motivation behind it, so that it is easily understandable, without having to use Laplace transforms, root locus, Bode diagrams, or Nyquist theorems.

So we start by asking ourselves.

What is the system to be controlled?

A system is a simplified representation of reality that we abstract to be able to work with it, because reality is too complex to work with as a whole. It normally represents a part of reality that we “mentally isolate” (although it can also be totally invented).

A system can be almost anything. The climate control of a building, the traction system of a car, the pumping equipment of a tank, an airplane, a spaceship, a robot… even the digestive system of a duck. Anything can be a system for you.

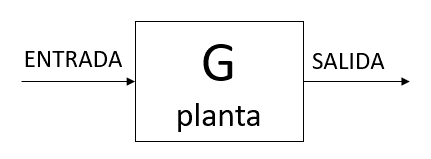

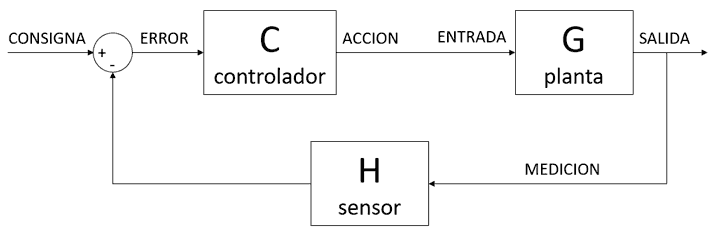

A system, which we will normally call a plant, has one or several inputs that represent actions we can act upon. It also has one or several outputs which are the parameters that are observable and measurable. In general, a system has many inputs and outputs, but we will normally simplify it to the most important ones.

Our plant also has a certain behavior. That is, performing an action will have a specific consequence on its outputs. Of course, the behavior can be as complicated as you can imagine. It can be nonlinear, have inertia, even pure delays (a time between when you apply the action and the system “finds out”), effects between multiple inputs.

The behavior of the plant can also be abstracted and modeled in a simplified way, in what we know as the transfer function. And we can represent it, for example, with an equation, a block diagram, a graphical or frequency representation, among others.

To make it more “fun”, our plant can have disturbances, that is, modifications in the environment that change its behavior. For example, in the building the outside temperature will change, in the car you can go up or down a hill, and in the reservoir it might start to rain.

In summary,

A system is a model of a portion of the universe, which has inputs and outputs, whose relationship between them follows a certain behavior and which is subject to possible disturbances.

And we represent it like this (and we remain “cool as a cucumber”).

What is a controller?

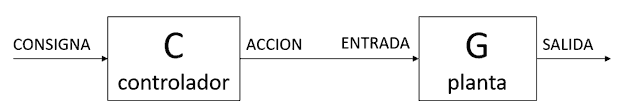

The controller is an element that we place before the inputs of our plant to act on them in order to achieve that the output has certain characteristics.

For example, you want to control the temperature of a building by acting on the boiler, the speed of a car by acting on the engine, or the level of a tank by acting on the pumping.

Logically, the input we are going to act on must have an influence on the output we want to control. If I am controlling a variable that is totally independent of what I am measuring, I can try all I want, but I won’t achieve anything!

The controller can be anything from a person, to an analog system, or a digital system. In automatic systems, we logically refer to some type of machine that controls the system autonomously without manual intervention.

The controller, represented along with the system, would look like this.

What characteristics do we want from the output?

The first and most obvious is that the output has a specific value which we will call the setpoint. For example, I want the temperature to be 24ºC, the car to go at 80km/h, or the water level of a reservoir to be 175m.

Of course, the setpoint does not have to be the same all the time. I might want the temperature to be 17ºC at night and 24ºC the rest of the time, the car to go at 50km/h when passing through a town, or want to empty the reservoir to 160m because I have to supply drinking water to the network.

But, besides the setpoint, there are other desired characteristics for the output. In general, I will want the output to be stable in the long term, to converge to the setpoint value, the response time to be fast, not to oscillate, not to overshoot the setpoint value at any moment.

And as it couldn’t be otherwise, or this would be too easy, I won’t be able to have them all at once, so I will have to reach a compromise between all of them. Although, if it comes to it, I might be willing to sacrifice some over others.

For example, maybe you don’t mind if the temperature of a building briefly reaches 24.5ºC, if that way the response time is shorter. But if at 180m of water the reservoir breaks, flooding a town and killing hundreds of people and puppies, perhaps overshoot is not tolerable and you prefer slow but safe.

Therefore, the desired characteristics for the output depend entirely on your system and what you want to do, and consequently on the controller you have to use.

What is a closed loop?

It’s a very nice way to name something very obvious. For a controller to work, it must have feedback. And what is that? Well, basically that the controller has to be able to “see” the output it is trying to control directly or indirectly.

Without feedback, a controller is not a controller, it’s more like a “declaration of good intentions blindly”. Imagine you have to control a variable, by moving a lever, and you don’t know what the variable measures. Well then, nothing to do! Eyes closed, lever in the middle, and let it be what God wills!

Alright, it’s clear that to control an output we have to be able to measure it. So we take the output and compare it with the setpoint to see the error we have. We use this error as the input to our controller. We represent it like this.

The error between the measurement and the setpoint can be because we haven’t yet managed to get the output to reach the setpoint, or because the setpoint has been changed.

Deep down it’s quite intuitive, it makes sense, doesn’t it? So why so much interest in the closed loop? Does the system change a lot by having that feedback branch from the output to the input? Well, yes, all kinds of very interesting things can happen (and some quite horrible ones).

With feedback, the global system (controller + plant) behaves in a totally different way. The output can range from tending placidly and obediently to the setpoint, to oscillating like crazy until something breaks.

And the difference between one output (absolute success in your control system) and the other (breakage, getting fired, and possible destruction of the universe) depends entirely on the controller you design. Cool, huh?

The intuitive version of the controller

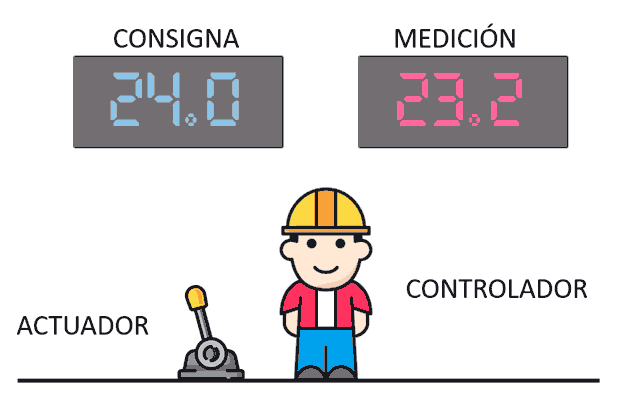

So, what the heck is a controller? A controller is you (in fact, your brain is an excellent controller), who has woken up in the middle of an empty room. In front of you is a table with an analog lever that accepts any value between 0 and 100, and on the wall two huge displays, one blue and one red.

The only thing you know is that the lever in front of you controls, in some way, the climate control system of a building. The blue number is the setpoint, that is, the temperature your boss asks you to have in the building. And the red value is the actual temperature measured at this moment.

You know absolutely nothing else. You don’t know if it’s a large or small building, how well insulated it is, nor the outside temperature, if it’s winter, what time it is, if it’s cloudy, if someone suddenly opens all the windows, if 100 people have just entered or if the building has become empty.

You also don’t know what effect the lever has on the building’s temperature. You don’t know if setting the lever to mid-range will light the equivalent of two matches, and the temperature will barely change. Or if, on the contrary, you have two spaceship reactors, and at half lever you are going to incinerate everyone.

In summary, we are going to assume that you have no prior information about the plant. The only thing we are going to warn you about is that your heating system is sufficient to reach the setpoint, at least under “normal” operation. Because if your actuator doesn’t have enough power, there’s little we can do to control the system.

It’s clear that if the red screen (measurement) were off, it would be much worse. If you only knew they wanted 24ºC, but not what temperature it is, nor what the plant is like, nor the effect your lever has… as we said before, without feedback you can only act blindly and cross your fingers.

Things change if the red screen turns on. Now, at least, you can compare measurement and setpoint (what we called error) and maybe we can even do something. Could you control the temperature, with this information? Of course you could, and that is, precisely, a controller.

How are you going to move the lever, based on what you see on both screens? A lot, a little? That is the controller design part, determining the response it will perform on the lever (actuator) as the values on the screens vary.

What possible strategies can we apply for controller design? Many. In the next post, we will see one of the simplest and most intuitive, on-off control with hysteresis. In the following one, we will see an intuitive approach to the PID controller, one of the most used controllers in the industrial field.

Download the code

All the code from this post is available for download on Github.