The lifecycle (or execution cycle) refers to the different stages a program goes through from its start to its completion. The entire process is what we call the program’s execution cycle.

The lifecycle can be very simple, like in a console application,

In this case, when we launch a program it:

- Starts

- Does things for a while

- Closes

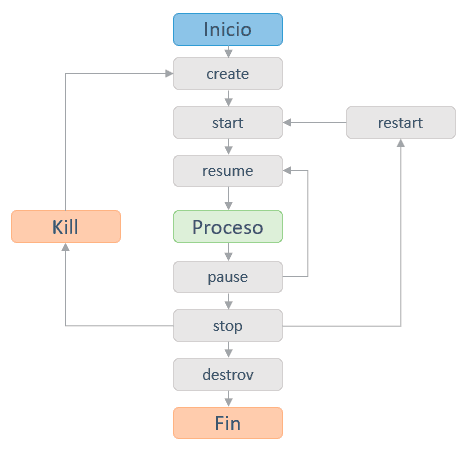

But they can become much more complex, as in the case of a mobile device application, or a game running on a game engine.

For example, the lifecycle of an Android application looks like this.

As we can see, it’s no longer as simple as start, run, and close. There are various ways to end a program, and it can even be suspended and resumed later.

The Role of the Operating System

During a program’s lifecycle, the operating system (OS) plays a fundamental role at each stage, (and when I say OS we should think “whatever we are using to run our program”).

On simpler machines (like an Arduino) the “OS” is simply a bootloader that launches the program we’ve run. Other more complex machines use lightweight operating systems like FreeRTOS.

If we’re talking about computers or mobiles, we have OSes like Windows, or Linux, or Android, (or whichever). Even if we are running a game engine, this will be an additional software layer between our program and the hardware.

In any case, our program is going to run “on top” of several layers of software (the topic is quite complex and we won’t go into more details today).

But it is important for you to know when your program’s execution life begins, how it runs, and when it ends.

Entry Point

The lifecycle of an application begins at the entry point, which is the starting point of the program’s execution.

At this stage, the OS is responsible for loading the program into memory and allocating the necessary resources for its execution. The OS also sets up the execution environment and provides the command-line arguments passed to the program (like input parameters).

In many programming languages, such as C++ or Java, the entry point is usually a function or method with a specific name, which indicates where the code should start executing.

If we take for example an example in C++, we see it has a main() method as the entry point.

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// here is the code that will execute at the beginning

}

This would be very similar in C# or Java, for example. In these languages, the program’s entry point is indicated with the main() method.

It is usually possible to change the name of the entry point in the project configuration, or as compilation options.

In the case of interpreted (or semi-interpreted) languages, in addition to the OS we have an additional software layer which is the language interpreter. Therefore, normally, in interpreted languages the program’s entry point is simply the first line of the program itself.

For example, in JavaScript it’s enough to do,

console.log("Hello, world!");

No further instructions are necessary because the interpreter is ready to execute the code as it arrives.

Code Execution

Once the program has been loaded into memory and the execution environment has been set up, the execution of the code itself proceeds. The program follows the instructions and performs the operations defined in the source code.

During this stage, the OS is responsible for managing execution time, allocating additional resources as needed, and ensuring a safe and protected execution environment.

The OS also provides access to various system functionalities and services, such as communication with input/output devices, file management, and interaction with other running programs. Furthermore, it monitors the program for possible errors or anomalous behaviors that could affect system stability.

Finally, in the case of interpreted languages, we also have the interpreter doing its work, which often also includes memory management, or input and output handling.

Exit Code

At some point the program will stop running. This could be because the machine where it’s running is shut down or restarted, or because the program finishes (we’ll ignore the part about shutting down the machine, because it’s not really a controlled “termination” of a program).

When a program finishes, it informs the OS that it has no more pending tasks to perform and that it has completed its function. To do this, it produces an exit code that indicates the state in which the program ended.

The exit code is returned to the OS and can be used by other programs or scripts to make decisions or perform actions based on the execution result.

The exit code generally has an integer value, where a value of 0 indicates that the program ran correctly without errors. Other non-zero values can indicate different types of errors or exceptional conditions, and their interpretation may vary depending on the program and the operating system.

After the program ends, with the exit code, the OS can take appropriate actions (for example, free the memory it had reserved for the process, or log if an error occurred during execution).

In interpreted languages, the OS is generally not informed that the program has ended. Because, really, the OS is running the interpreter, not the program. So the process termination management is done by the interpreter itself, but it continues running.