When working with variables in programming, it is essential to understand the variable’s scope. This is one of the topics that many programmers struggle to understand (when, in reality, it’s very simple).

The scope of a variable is the context in which a variable exists and can be used. Outside its scope, the variable does not exist (and therefore, we cannot use it).

Just as we saw when looking at a program’s lifecycle, a variable has its own “lifecycle.” In general, during our program,

- We declare / create the variable

- We use the variable

- The variable is destroyed

The area where we can use the variable is its scope. In general (spoiler alert!) in almost all modern languages, the variable exists from the moment it is created until the block in which it is defined ends.

It’s intuitive to think that we cannot use a variable before creating it (although we will see that some languages are a bit special, right JavaScript?).

The other missing factor: When does the variable cease to exist? Well, unless we manually free it, the variable is automatically destroyed when exiting the block where it was created.

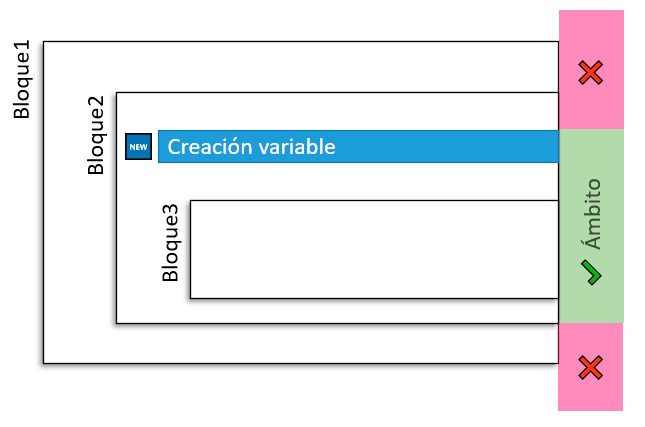

So the scope of existence of the variable includes all the instructions and nested blocks found between the creation and destruction of the variable, which normally occurs at the end of the block where it was created.

Which, put into code form, looks something like this:

// here NOT available ❌

{

// here NOT available ❌

int myVariable = 5;

// here IS available ✔️

{

// in this inner block IS also available ✔️

}

}

// here NOT available ❌

Examples of Variable Scope in Different Languages

Let’s look at variable scope in different languages.

In C#, the scope of a variable can be a code block, a function, or the entire class:

class ExampleClass

{

int classVariable = 5;

void ExampleFunction()

{

int functionVariable = 10;

if(condition)

{

int blockVariable = 15;

}

}

}

Here

classVariablewould be available throughout theExampleClassclassfunctionVariablewould be available within theExampleFunctionfunctionblockVariablewould be available within the conditional

This behavior is more or less the standard in all programming languages.

For example, in Python

def example():

functionVariable = 10

if True:

blockVariable = 15

print(blockVariable)

print(functionVariable)

JavaScript deserves its own “honorable mention” when talking about variable scope. In its early versions, it had the “brilliant idea” of being different from the others (spoiler, it didn’t go well 😅).

Explaining it in depth I’ll leave for when I do a JavaScript course, but in short, initially variables in JavaScript had function scope, not block scope (pause for applause 👏👏).

if (true) {

var x = 20; // this has function scope, not if scope 😱

}

This led to many weird and unexpected situations. It caused so many problems that in later versions they had to try to fix it by introducing let and const, which work with block scope.

if (true) {

let x = 20; // this has if scope

}

In summary, there are few languages where variable scope is not the block (that I can think of, BASIC and JavaScript). But since JavaScript is so widely used and important, it seemed important to highlight it.

Global Variables and Local Variables

In many programming languages it is possible to define global variables, which can be accessed from anywhere in the program.

For example, suppose an Arduino program (which is based on C++)

int globalVariable = 10; // Declaration of a global variable

void setup() {

}

void loop() {

// Show the value of the global variable on the serial monitor

Serial.println(globalVariable);

}

For example, here we would have an example of global variables in Python

x = 10

def myfunc():

# Show the value of the global variable in the console

print(x)

Although Python also has its own “special” quirks. If we wanted to modify the value of x, instead of just consulting it, we would have to use the global keyword. But that’s for when I do a Python course.

In JavaScript

let globalVariable = 10;

function updateGlobalVariable() {

// Show the value of the global variable in the console

console.log(globalVariable)

}

In general, almost all languages have global functions implemented, one way or another, or with their language-specific peculiarities. But they have them.

Best Practices Tips

It is often said that using global variables is a bad practice. Well, it’s not always a bad practice. In fact, not only are they useful, but they are necessary for the program to work (the entry point, for starters, is a global variable).

If you think about it, there is actually no conceptual difference between a global variable and a local variable. A global variable also has its scope. It’s just that since it’s outside of any block, its “block” is the entire program.

What is true is that abusing global variables is a bad practice. In general, we should always use local variables whenever possible, and use global variables in the few cases where it is truly essential.

Let’s look at a very simple example, in a hypothetical machine that reads a temperature and uses a function to modify it.

int rawTemperature; // Declaration of a global variable

void correct_temperature() {

rawTemperature *= 2; // Do anything with your global variable

}

void loop() {

rawTemperature = 10;

correct_temperature();

}

Making all variables global is pretty nast… well, you know what I mean. It’s much better if instead, we use local variables, and each function has defined the parameters it needs and what it returns.

int correct_temperature(int temperature) {

return temperature * 2;

}

void loop() {

int rawTemperature = 10;

int corrected_temperature = correct_temperature(rawTemperature);

}

In the long run, the code is much more maintainable, better isolated, reusable, etc., etc.

Low-Level Explanation Advanced

Let’s try to briefly explain how variable scope works and the reasons for its existence, at a low level.

In compiled languages like C++, when we create a variable inside a block, it is stored on the stack. Regardless of whether the variable’s “content” goes to the heap, the variable itself always goes to the stack.

Then the block performs its actions and its tasks. When the block ends, the stack must be clean and in a neutral state. During the process, local variables are removed.

That is, at a low level, the fact that variables are always attached to the block in which they are created is an imposition due to how the processor works.

In semi-compiled languages like Java or C# or interpreted ones like Python, it wouldn’t necessarily have to be this way. Here, the memory manager or the interpreter could decide to keep the variable after the block ends.

In fact, we’ve seen that JavaScript, at first, didn’t follow this norm… and that’s how it went for them.

However, the same rules have been kept because they are intuitive and practical. The fact that a variable is local and ceases to exist when it leaves its scope seems to make sense, doesn’t it?

This favors code reuse and reduces the possibility of errors. Therefore, more ‘modern’ programming languages continue to maintain the same rules, although, unlike lower-level languages, they are not strictly forced to comply.