By this point in our journey through the Raspberry Pi tutorials, you’ve probably encountered that certain commands start with ‘sudo’. In this post, we’ll see what ‘sudo’ is and how to use it to run commands with root permissions.

Basically, ‘sudo’ is an application that allows us to run another command with elevated or administrator permissions. It’s necessary to prefix certain commands with it so we can execute them.

But to understand its necessity, let’s briefly look at what a user and a super user are, and what role ‘sudo’ plays in all this.

Users and Super Users

As we know, one of Linux’s strong points is its security. And any security system is based on good user and permission management, as we’ll see in the next post in the series.

In Linux, we have “normal” users who, generally, have permission to run programs and interact with files in their ‘home’ folder. For example, the default user ‘pi’ we access Raspberry with is a normal user.

But Linux also has system administrator users, also called Super Users or ‘roots’. We generally use both terms interchangeably. Administrators, basically, have permission to perform any action on the system.

During the installation of a Unix system, at least one Super User is created, usually with the username ‘root’, ‘admin’, ‘administrator’, or ‘superuser’. In Raspbian, the default Super User is ‘root’.

Calling a Super User ‘root’ originates from them having access to the system’s root, i.e., /root

Of course, the most critical, important, and dangerous system commands must be executed by someone with Super User permissions. Super Users, unlike a normal user, can also act on other users’ accounts.

However, it wouldn’t be very practical if only users logged in as root could perform these tasks. Sometimes it’s useful to grant other users permission to run administrator applications.

But if we want certain users to be able to run these commands, giving them the root user password wouldn’t be very practical either. It also wouldn’t be practical to have to log out and log back in as root to run the command, having to navigate back to where we were before, etc. This is where the sudo command comes into play.

What is ‘Sudo’?

Sudo (Super User Do) is an application developed in 1980 by Bob Coggeshall and Cliff Spencer, and currently maintained by Todd Miller with the collaboration of Chris Jepeway and Aaron Spangler.

This utility, incorporated into Unix systems and derivatives (Linux, Mac OS, etc.) allows running a command with the privileges of another user. This includes running programs as root, which is the function we’ll use ‘sudo’ for most frequently.

How to use sudo

To run a command with the privileges of another user, we use the following command:

sudo -u otroUsuario comando

Where ‘otroUsuario’ is the name of the user we want to emulate, and ‘comando’ is the command to execute.

If we omit the username, which is the most common syntax, we will run the command with root permissions.

sudo comando

If you’ve typed a command and realize you need Super User permissions, you can invoke the last command simply by doing:

sudo !!

Another possibility to gain super user permissions would be to use the command:

sudo su

This grants us super user permissions for the session, until we execute the command:

exit

Which will remove the elevated permissions and return us to our sad existence as a common user. But this is not a good habit and we should get used to doing it only when absolutely necessary.

Who can use ‘sudo’

Logically, controlling who can run the ‘sudo’ application is vital for system security. When executing ‘sudo’, the first thing the application does is verify in a configuration list that the current user can run ‘Sudo’.

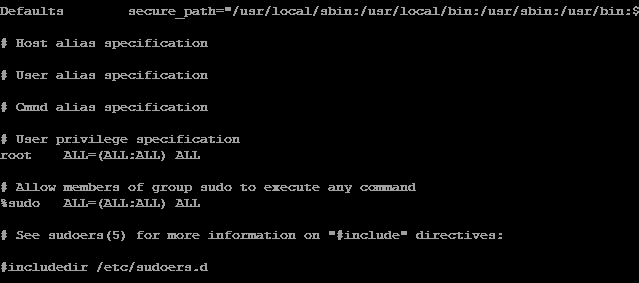

The ‘sudo’ configuration is saved in the ‘sudoers’ file located at ‘/etc/sudoers’. However, manual editing of the ‘sudoers’ file is strongly discouraged. Instead, we should use the command:

sudo visudo

‘visudo’ is an application that allows safe editing of the ‘sudoers’ file. First, it locks the file during editing so two people don’t modify it simultaneously. On the other hand, before saving the ‘sudoers’ file, it checks that the syntax is correct and stops if it detects any defect.

The ‘sudoers’ file has its own quite particular syntax and many options to configure. Let’s just see a brief summary of the many available options.

When editing the ‘sudoers’ file, you’ll see it looks something like this:

User privilege specification

root ALL=(ALL) ALL suse ALL=(ALL) ALL pi ALL=(ALL) ALL

Where the simplest syntax for a ‘sudo’ permission is:

userName ALL=(ALL

- userName indicates the user to whom the rule applies

- First ‘All’ indicates that the rule applies on all hosts

- Second ‘All’ indicates they can run commands as all users

- Third ‘All’, can run commands as all user groups

- Last ‘All’ indicates they can run all commands

So, for example:

pi ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL

Means that the user ‘pi’ can run on all hosts, as any user, any command, and does not have to enter the password.

Of course, there is much more we could explain about the ‘sudoers’ file, which has many more options and parameters we can configure. However, that is beyond the scope of this post. If you’re more interested, you can consult the program’s documentation.

The Responsibility of the SuperUser

We couldn’t fail to mention the minimum rules to respect when acting as a root user:

- Respect others’ privacy

- Think before you type

- With great power comes great responsibility

Which is a reminder of the responsibility of being a Super User. First, keep in mind that when you mess up, there’s nothing to protect you from mistakes. You can break the system all by yourself.

That’s why it’s good to get used to running commands with elevated permissions only when necessary. The rest of the time, work as a ‘normal’ user.

Finally, of course, you shouldn’t do anything in others’ accounts that you wouldn’t want done in yours.

That’s it for the post about users, super users, and the use of the almost indispensable ‘sudo’ application. From here on, we’ll use ‘sudo’ frequently, and you’ll soon get used to it.

In the following posts, we’ll see user and password management, and user group management, two fundamental aspects for maintaining our system’s security.