Recently, there has been a growing interest in devices called FPGAs, as an alternative to microprocessor-based electronics.

In this post, we will see what an FPGA is, what are the reasons for its rise and popularity in the geek/maker world. In the future, we will delve into Open Source FPGAs with the Alhambra FPGA.

What is an FPGA?

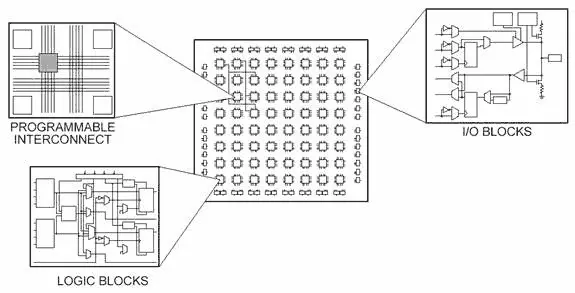

It is a type of electronic device formed by functional blocks connected through an array of programmable connections.

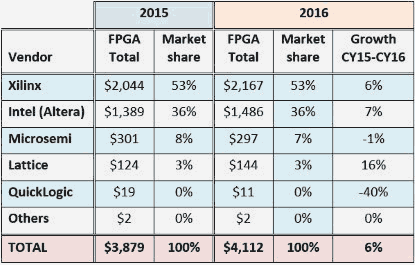

FPGAs were invented in 1984 by Ross Freeman and Bernard Vonderschmitt, co-founders of Xilinx. Some of the main manufacturers are Xilinx, Altera (purchased by Intel in 2015), MicroSem, Lattice Semiconductor or Atmel, among others.

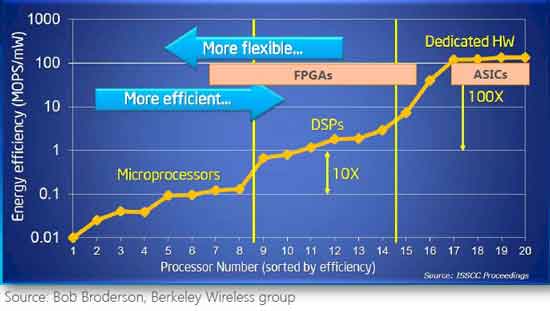

FPGAs are slower than an ASIC (Application-Specific Integrated Circuit), specific processors developed to perform a certain task. However, the great flexibility of being able to change their configuration makes their cost lower both for small manufacturing batches and for prototyping, due to the enormous expense required to develop and manufacture an ASIC.

FPGAs are used in industries dedicated to the development of digital integrated circuits and research centers to create digital circuits for prototyping and small series of ASICs.

How is it different from a processor?

Although at first glance a processor and an FPGA seem to be similar devices, because both are capable of performing certain tasks, the truth is that upon closer examination it is almost easier to find differences than similarities.

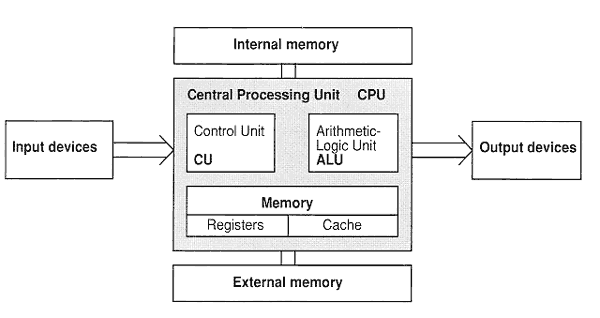

To get into the topic, let’s recall very briefly how a processor works. A processor contains a series of instructions (functions) that perform operations on binary operands (add, increment, read and write from memory). Some processors have more instructions than others (associated with the processor’s internal circuitry) and this is one of the factors that determine their performance.

On the other hand, it contains a series of registers, which hold the input and output data for the processor’s operations. Additionally, we have memory to store information.

Finally, a processor contains an instruction stack, which holds the program to be executed in machine code, and a clock.

In each clock cycle, the processor reads the necessary values from the instruction stack, calls the appropriate instruction, and executes the calculation.

When we program the processor, we use one of the many available languages, in a format that is understandable and convenient for users. During the linking and compilation process, the code is translated into machine code, which is stored in the processor’s memory. From there, the processor executes the instructions, and thus our program.

However, when programming an FPGA, what we are doing is modifying a connection matrix. The individual blocks are made up of elements that allow them to adopt different transfer functions.

Together, the different blocks, connected by the connections we program, cause an electronic circuit to be physically constituted, similar to how we would do it on a breadboard or when manufacturing our own chip.

As we can see, the substantial difference. A processor (in its many variants) has a fixed structure and we modify its behavior through the program we write, translated into machine code, and executed sequentially.

However, in an FPGA we vary the internal structure, synthesizing one or several electronic circuits inside it. By “programming” the FPGA, we define the electronic circuits we want to be configured inside it.

How is an FPGA programmed?

FPGAs are not “programmed” in the sense we are used to, with a language like C, C++, or Python. In fact, FPGAs use a different type of language called a descriptive language, rather than a programming language.

These descriptive languages are called HDL or Hardware Description Language. Examples of HDL languages are Verilog, HDL or ABEL. Verilog is Open Source, so it will be one of the ones we hear about most frequently.

Descriptive languages are not exclusive to FPGAs. On the contrary, they are an extremely useful tool in chip and SoC design.

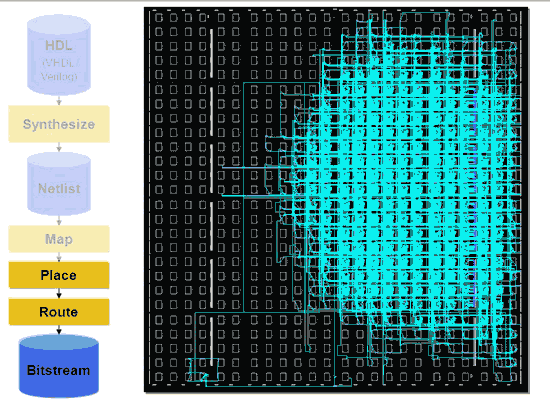

Subsequently, the integrator (roughly speaking, the equivalent of the “compiler” in programming languages) translates the description we have made of the device into a synthesizable (realizable) device with the FPGA blocks, and determines the connections that need to be made.

The connections to the FPGA are translated into a specific communication pattern (bitstream) specific to the FPGA, which is transmitted to the FPGA during programming. The FPGA interprets the bitstream and configures the connections. From that moment on, the FPGA is configured with the circuit we have defined/described.

HDL languages have a steep learning curve. The main difficulty is that they have a very low level of abstraction, as they describe electronic circuits. This causes projects to grow enormously as the code increases.

Manufacturers provide commercial tools for programming their own FPGAs. Currently, they set up complete environments with a large number of tools and functionalities. Unfortunately, most are not free, or are only free for some of the manufacturer’s FPGA models. Unfortunately, they are not free, and are tied to the architecture of a single manufacturer.

With the development of FPGAs, other languages have appeared that allow a higher level of abstraction, similar to C, Java, Matlab. Examples are System-C, Handel-C, Impulse-C, Forge, among others.

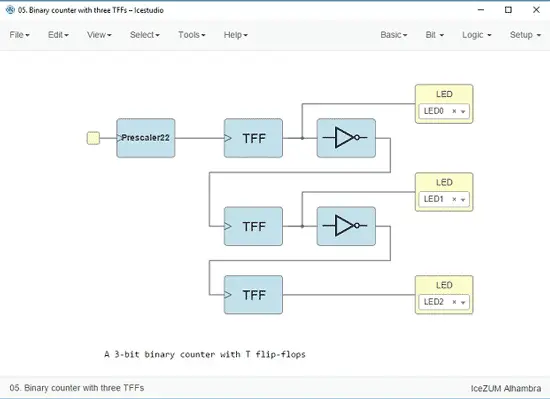

With the evolution in FPGA development, tools focused on graphical programming of FPGAs have also appeared, such as LabVIEW FPGA, or the Open Source project IceStudio developed by Jesús Arroyo Torrens.

Finally, some initiatives have attempted to perform conversion from a programming language to HDL (usually Verilog), which can then be loaded into the FPGA using its tools. Examples are the Panda project, the Cythi project, or MyPython, among others.

Why does an FPGA need to be simulated?

When we program a processor, if we make a mistake, there are usually no serious problems. Often we even have an environment where we can do Debug and trace the program, set breakpoints, and see the program flow.

However, when programming an FPGA, we are physically configuring a system and, in case of an error, we could cause a short circuit and damage part or all of the FPGA.

For this reason, and as a general rule, we will always simulate the design to be tested before loading it onto the real FPGA.

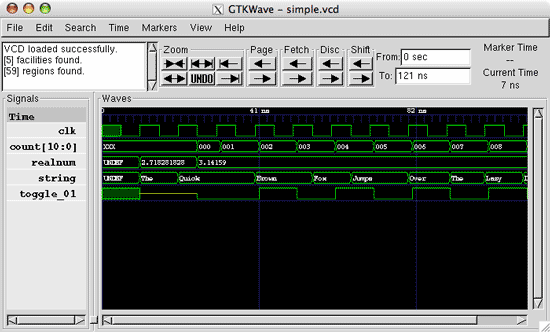

For simulation, descriptive languages are also used, in combination with some software that allows simulating and graphing the FPGA’s response. An example is GTKWave.

Commercial suites usually integrate the simulation tool within the programming environment itself.

What is the price of an FPGA?

Logically, there is a wide range of prices but, in general, they are not cheap devices. Speaking of the domestic sector (the ones we are going to buy), they are in the range of approximately 20 to 80 euros.

To put it in context, it is much more expensive than an Arduino Nano (16Mhz) or an STM32 (160Mhz) that we can buy for 1.5€, a Node Mcu ESP8266 (160Mhz + WiFi) that we can buy for 3.5€. They are even much more expensive than an Orange Pi (Quad 800 Mhz + WiFi), which can be found for about 20€.

How powerful is an FPGA?

It is difficult to define the computing power of an FPGA, given that it is something totally different from a processor like the one we can find in an Arduino, an STM32, an ESP8266, or even a computer like a Raspberry PI.

FPGAs excel at performing parallel tasks, and at extremely fine control of the timing and synchronization of tasks.

Actually, it’s better to think in terms of an integrated circuit. Once programmed, the FPGA physically constitutes a circuit. In general, as we have mentioned, an FPGA is slower than the equivalent ASIC.

The power of an FPGA is given by the number of available blocks and the speed of its electronics. In addition, other factors come into play, such as the constitution of each of the blocks, and other elements like RAM blocks or PLLs.

To continue the comparison, the speed of a processor is determined by its operating speed. Furthermore, it must be taken into account that a processor frequently requires between 2 to 4 instructions to perform an operation.

On the other hand, although FPGAs normally incorporate a clock for performing synchronous tasks, in some of the tasks the speed is independent of the clock, and is determined by the speed of the electronic components that form it.

As an example, in the well-known Lattice ICE40 FPGA, a simple task like a counter can run at a frequency of 220Mhz (according to the datasheet). In a single FPGA, we can have hundreds of these blocks.

Which is better, Arduino, FPGA or Raspberry?

Well… Which is better, a spoon, a knife or a fork? They are different tools, each excelling at different things. Certain tasks can be done with both, but in some cases, it is much more suitable and efficient to use one of them.

Fortunately, the scientific and technical field is not like a football match or politics… we don’t have to choose a side. In fact, we can use them all even simultaneously. Thus, there are devices that combine a processor with an FPGA to provide us with the best of both worlds.

In any case, FPGAs are a very powerful tool and sufficiently different from the rest to be interesting in themselves.

Can I make a processor with an FPGA?

Of course you can. An FPGA can adopt any electronic logic circuit, and processors are electronic circuits. The only limitation is that the FPGA has to be large enough to house the processor’s electronics (and processors are not exactly small).

There are projects for small processors that can be configured in an FPGA. Examples are MicroBlaze and PicoBlaze from Xilinx, Nios and Nios II from Altera, and the open source processors LatticeMicro32 and LatticeMicro8.

There are even projects to emulate historical processors on FPGAs, such as the Apollo 11 Guidance Computer processor.

Emulating a processor on an FPGA is an interesting exercise both for its complexity and for learning. Furthermore, it is interesting if we want to test our own processor or our ideas.

However, in most cases, it is simpler and more economical to combine the FPGA with an existing processor. There are very good processors (AVR, ESP8266, STM32).

Why are FPGAs on the rise?

First, because technologies become cheaper over time. Not many years ago, an automation device with a capacity similar to an Arduino could cost hundreds or even thousands of euros, and now we can find it for a few euros.

Similarly, FPGAs have been gaining popularity in the industry. As production increases, they have appeared with greater capacities and functionalities. There are even ranges intended for embedded devices or mobile applications. All this encourages the price drop of certain FPGA models.

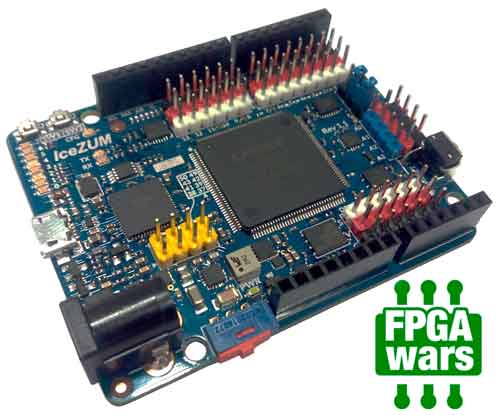

On the other hand, the main reason for the rise in the popularity of FPGAs in the domestic/maker field is the reverse engineering work carried out by Clifford Wolf on the Lattice iCE40 LP/HX 1K/4K/8K FPGA, which gave rise to the IceStorm project.

The IceStorm project is a toolkit (consisting of IceStorm Tools + Archne-pnr + Yosys) that allows the creation of the bitstream necessary to program an iCE40 FPGA with Open Source tools.

Clifford’s work was done on an IceStick, a development board with an iCE40 FPGA, due to its low cost and small technical characteristics, which allowed the reverse engineering work.

It was the first time that an FPGA could be programmed with Open Source tools. This allowed the generation of a growing community of collaborators that have resulted in wonders like IceStudio or Apio.

Keep in mind that other FPGAs require investments of hundreds of euros to buy the FPGA and up to thousands of euros for the software.

Let’s say that, saving distances, the IceStorm project and the Lattice ICE was the beginning of a revolution in the FPGA field similar to the one Arduino started with Atmel’s AVR processors, and which has made it accessible to domestic users.

Do FPGAs have a future or are they a passing fad?

Well, even without a crystal ball, it is most likely that FPGAs are devices that will be useful, at least, in the medium and short term. As we said, they are frequently used to facilitate the design and prototyping of ASICs. Furthermore, they are expanding their scope of application, from applications with heavy calculations (vision systems, AI, autonomous driving) to lightweight versions for mobile devices.

As an example of their viability, consider that Intel invested 16.7 billion dollars in the purchase of Altera. Market estimates point to an estimate of 9000-10000 million dollars for 2020, compared to 6000-7000 million dollars in 2014, and an annual growth of 6-7% (well above the 1-2% average growth for the semiconductor sector).

Speaking of the future (years) in which FPGAs become cheaper and popularized, we can even imagine hybrid FPGA and processor systems (or even totally FPGA) where software can reconfigure the hardware, creating or undoing processors, or memory, according to needs.

The real question is: do Open Source FPGAs and the “domestic” field have a future or are they a passing fad?

The short answer is, we hope so. The long one is that, as of today, we only have one FPGA (the iCe40) available compatible with Open Source tools, and it is actually a fairly small and low-power FPGA.

If the technique continues to advance and the community is not strong enough to generate an ecosystem that pushes FPGAs towards Open Source, there is a certain risk that it will remain a passing bubble.

The best way is to encourage the expansion of this type of device, and to generate a strong community that fosters the popularization of this technology. And if possible, by creating and improving the available Open Source tools for FPGAs.